Cigars and the Long Arc of a Rolled Leaf: Origins, Diffusion, and Industrial Reinvention

The cigar is a deceptively simple object: a leaf wrapped around other leaves, set alight, and enjoyed slowly. Yet behind that simplicity sits a sprawling history—part botany, part empire, part craft tradition, and part modern branding. To trace the cigar’s origins is to watch a cultural practice travel across oceans, mutate through language and fashion, and eventually split into two worlds: the mass-produced everyday cigar and the premium hand-rolled ritual.

Indigenous beginnings and the first great transfer

Long before cigars became emblems of European leisure, tobacco was already integrated into Caribbean life. When Europeans arrived in the late 15th century, they encountered rolled and dried tobacco leaves being smoked in forms that strongly resemble early cigars. The key point is not merely that tobacco existed, but that a method existed: preparation, rolling, drying, and combustion were already established techniques—knowledge embedded in practice.

By the early 1500s, European sailors had begun adopting the habit. This is one of those moments where history moves fast: a portable ritual, requiring little equipment and producing a memorable effect, crosses a cultural boundary with unusual ease. Once a practice can be repeated socially—and carried in a pocket—it becomes highly transmissible.

Europe adopts tobacco: status, novelty, and chemistry

As tobacco use spread across Europe, influential figures helped normalize it, turning an exotic curiosity into a fashionable habit. Jean Nicot played a notable role in popularizing tobacco in France; his name later became attached to nicotine, the plant’s most famous alkaloid. In England, Sir Walter Raleigh helped establish tobacco as a widely known import, and pipe smoking grew into a defining early modern style.

An important phase in this diffusion involved tobacco being regarded as medicinal. In the mid-1600s, as cultivation expanded into North America, tobacco was often described in therapeutic terms. This tendency was common in early modern Europe: unfamiliar plants were frequently framed as remedies before later being moralized as indulgences—or, more realistically, both at once. Calling something “medicine” tends to lower cultural resistance and helps it slip into polite society.

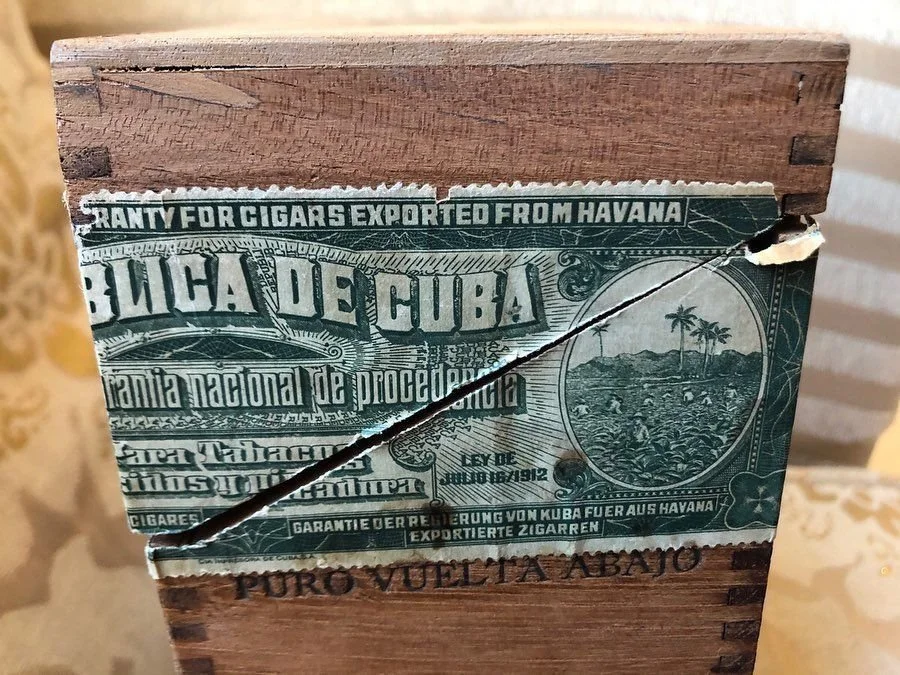

Cuba, Spain, and the birth of the “modern” cigar

Cuba became central early on, with Spanish colonists cultivating tobacco there between roughly 1550 and 1600. But the cigar’s “modern” identity—its recognizable form, its social packaging—was closely tied to Spain. Seville, in particular, is often cited as a birthplace of the modern cigar in the 18th century, and cigars were even known as “Sevillas.”

That naming matters. When a product becomes associated with a city, it gains an origin story that can be traded on—an early form of branding and quality aura. It is also a subtle form of cultural ownership: the leaf may come from elsewhere, but the identity can be anchored to a metropolitan center where the commodity is refined, standardized, and sold.

War as a distribution network: from “Sevillas” to “segars”

History has a habit of using wars as unintended delivery systems for culture. During the Peninsular War against Napoleon, British soldiers encountered and adopted the habit of smoking cigars. They brought it home, spreading the practice in England after returning. In the process, “Sevillas” became “segars”—a small linguistic mutation that signals something larger: once a community renames a thing in its own mouth, the habit begins to feel native.

This is one of the cigar’s recurring themes: it moves through bodies before it moves through institutions. Soldiers, sailors, migrants, and factory workers often do as much cultural work as diplomats and merchants.

The 19th century: factories, migration, and the cigar as a working-class engine

By the 19th century, cigar smoking was widespread and cigarettes were still comparatively rare. The cigar was no longer merely a curiosity or a courtly accessory; it was a mass cultural object supported by large-scale manufacturing. Factories employed enormous numbers of workers, and cigar-making became a pillar of regional economies.

Political turbulence also reshaped the industry. During Cuba’s Ten Years’ War, many manufacturers moved operations from Cuba to Florida. The result was the rise of places like Ybor City near Tampa, which became a major center of cigar production and, by some accounts, the largest cigar factory hub in the world at that time. This was globalization before the word became fashionable: expertise, labor, and capital relocating in response to risk.

At this scale, cigars were being produced in quantities that are hard to visualize—hundreds of millions annually. The cigar had become infrastructure: an economic system as much as a product.

1929: the apex of hand-rolled production

A striking snapshot arrives in 1929, when cigar workers in Ybor City and West Tampa rolled over 500 million cigars. At the same time, there were tens of thousands of cigar-making operations across the United States. This period is often described as the climax of hand-made cigar production.

That framing is important. “Climax” implies a turning point. The hand-rolled cigar is not simply a technique; it is a labor culture, a skill economy, and a social world. When a craft reaches peak scale, it becomes vulnerable to mechanization—not because the craft becomes worse, but because the market demands cheaper uniformity.

After the 1940s: machines change the meaning of “premium”

From the 1940s onward, machine-made cigars dominated volume. With that shift, a clear cultural divide emerged: premium hand-rolled cigars became one category, while machine-made cigars became another, often sold in packs at everyday outlets such as drugstores or gas stations.

This is one of the cigar’s great ironies: mass production helped invent the modern idea of “premium.” When machines flood the market with standardized products, hand-making becomes legible as rarity, tradition, and human attention. The term “premium” doesn’t just describe materials; it describes a story—of craft continuity in a world optimized for speed.

Where a cigar is purchased also shapes its meaning. A specialist environment implies ritual and expertise; an everyday retail environment implies convenience and habit. The same object shifts identity depending on its social setting.

The 1990s cigar boom: media, lifestyle, and scarcity

The mid-1990s saw a resurgence in cigar consumption—particularly in premium cigars—marked by rising imports and sharply increased sales. The surge created shortages of both raw materials and finished products, a classic sign that demand had outpaced the industry’s capacity to respond quickly.

This period also illustrates how media can manufacture taste. The founding of Cigar Aficionado in 1992 helped transform cigars into a lifestyle category with a public vocabulary: ratings, prestige cues, celebrity proximity, and connoisseurship. When a product gains a media ecosystem, it gains an interpretive framework—people are no longer just buying cigars; they are buying membership in a narrative.

Scarcity intensified that narrative. Short supply does not merely raise prices; it raises attention. It encourages collecting, status signaling, and the sense that a cigar is not simply a consumable but a curated experience.

Why the cigar endures

Across its long history, the cigar has repeatedly reinvented itself without losing its essential premise: a slow technology of pleasure made from an ordinary plant, elevated by knowledge. It began as an Indigenous practice observed and adopted, spread through sailors and soldiers, matured through colonial cultivation and metropolitan standardization, scaled through factories and migration, and then divided into mass and premium identities in the age of machines. Later, it was recharged by modern lifestyle media and scarcity economics.

The cigar endures because it is not only a product. It is a ritual object. It compresses time—asking for patience in a world that trains us to rush—and turns smoke into meaning: a private pause, a social signal, a craft tradition, and, occasionally, a small act of resistance against the frantic tempo of modern life.